If you start using weekly or bi-weekly formative assessments to guide instruction and remediation right now, you can increase the number of students scoring “proficient” or better on the state exam by 10-25%.

Outlandish? Hardly. This is exactly what is happening with the schools and teachers I am working with today.

The Academic Research

Research shows that teachers who modify their instruction and lessons based on frequent in-class assessments have higher-performing students than those who don’t (Perie, Marion, & Gong, 2009; Stiggins, 2005). And yet most teachers don’t do this, and it’s not because they’re bad teachers (Coburn & Talbert, 2006).

More often, it is because their districts are still focused on supporting an assessment legacy long past: summative assessments. Even when principals try to support teachers using data to drive instruction, they are stymied because principals need the support of districts in order to block out time for data analysis and collaboration among teachers, and also find and fund professional development training in personalized data-driven instruction.

My own Findings

Since the fall of 2015, I have been working with principals and teachers to implement frequent formative assessments. Sometimes frequent assessments are already part of the instructional plan, but the data aren’t being well-utilized. More often, frequent formative assessments are intended to be used, but aren’t being done because of logistical issues.

In both cases, however, making the simple changes needed to drive instruction based on real-time feedback from frequent formative assessments have almost always resulted in significant measurable gains on state summative tests. At the end of this report, there is a link to a checklist for formative assessment that will give you plenty of insight into how to get these outcomes for yourself.

Why Don’t Frequent Formative Assessments Work in Practice?

#1 – Data is gathered infrequently

When formative assessments are infrequent (and I mean less than once every 2 weeks), they provide important information on how the instructional program should be adjusted for the upcoming school year, but they have no impact on the school year currently happening because by the time the data arrives, the teacher has moved on and students have fallen behind (Hueber, 2009).

#2 – Don’t inform learning and teaching in real-time

Some formative assessment tools don’t give immediate results in the classroom. It might seem fast to get your results back in a day. But actually that’s not fast enough to engage students, and it’s not fast enough to plan remediation.

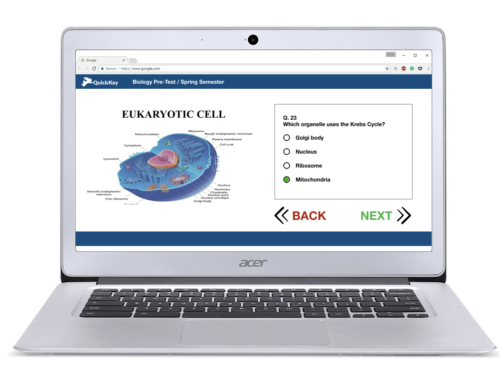

#3 – Too difficult to use

Most formative assessment programs require the creation of new assessments from an item bank or from an old test that needs to be copy/pasted into a new system. This is a lot of friction, and a lot to ask of a busy teacher! Not only that, but when a tool forces all students to take a quiz on a Chromebook, for example, it can be hard for every teacher to get every student on-device, on-time, without taking too much class time away.

How to Fix it

Because even formative assessment data can arrive too late to make an impact, critical instructional decisions cannot be based upon them (Stiggins, 2005). On the other hand, rapid formative assessments are so powerful that “when implemented well, formative assessment can effectively double the speed of student learning,” according to Wiliam 2007.

Although there is an ongoing tradition in schools to give assessments, there is limited access to timely standards-aligned data that is useful for informing instruction. Wayman and Stringfield (2006) stated that schools are in “the paradoxical situation of being both data rich and information poor” (p. 464).

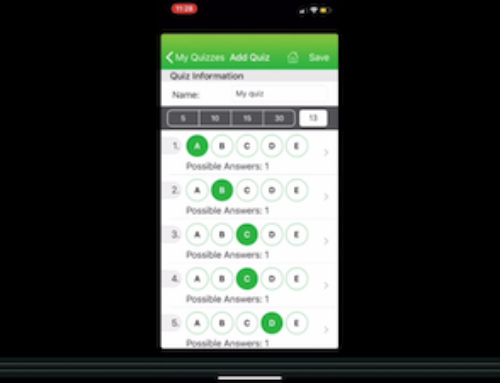

Using a formative assessment platform provides educators with valuable data that allows them to link student achievement to instructional objectives (Halverson, 2010). This is especially true of platforms that offer a way to track the data (and standards, and mastery) across interim and formative assessments. These platforms allow teachers to be both data and information rich.

So how do you select a good formative assessment system? Get the checklist here.

References

Coburn, C., & Talbert, J. (2006). Conceptions of evidence use in school districts: Mapping the terrain. American Journal of Education, 112(4), 469-495.

Halverson, R. (2010). School formative feedback systems. Peabody Journal of Education, 85(2), 130-146.

Huebner, T. A. (2009). What research says about … balanced assessment. Educational Leadership, 67(3), 85-86.

Perie, M., Marion, S., Gong, B. (2009). Moving toward a comprehensive assessment system: A framework for considering interim assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 28(3), 5-13.

Stiggins, R. (2005). From formative assessment to assessment for learning. A path to success in standards-based schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 87(4), 324-328.

Wayman, J., & Stringfield, S. (2006) Data use for school improvement: school practices and research perspectives. American Journal of Education, 112(4), 463-468.

Wiliam, D. (2007). Changing classroom practice. Educational Leadership, 65(4), 36-42.